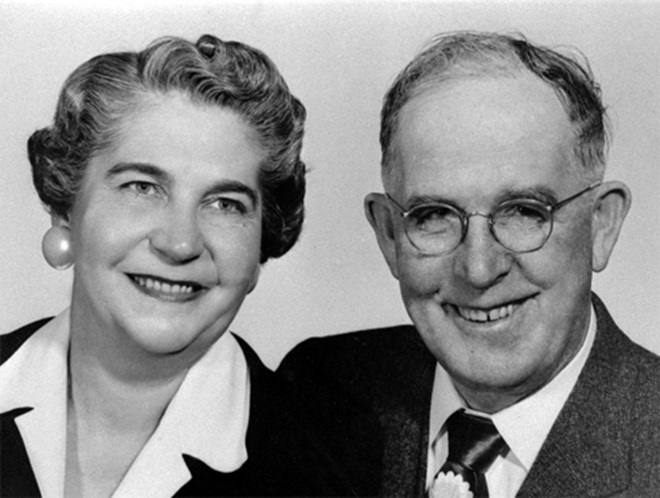

Anderson, Anton A.

1892-1960 | Civil Engineer, Surveyor, City Councilman, and Mayor of Anchorage (1956-1958)

Anton A. Anderson was a civil engineer working on railroads, dams, and tunnels in Alaska, including his service with the Alaskan Engineering Commission (AEC), Alaska Railroad, U.S. Army, and other federal and local agencies. He became known as “Mr. Alaska Railroad”[1] due to his work in surveying and engineering much of the railroad line and also surveying the original Anchorage townsite. During the 1930s, he was location engineer for sites for Matanuska Valley Colony projects. He was the principal civilian engineer for the U.S. Army during World War II, and headed construction of a railroad spur tunnel, the Whittier Tunnel, connecting Whittier to Portage. After many years of federal service, he served as mayor of Anchorage from 1956 to 1958.

Robert B. Atwood, the editor of the Anchorage Times, said these words about Anton Anderson:

“The professional achievements of Anderson are often overshadowed by his personality and his warm and friendly relationships with people. He was half Swede and was built big like a Swede, but the other half was Irish, and it showed in his bright Irish eyes that were always smiling, and in his Irish wit.”[2]

Anton Albert Anderson was born on June 28, 1892 at Upper Moonlight, Ahaura, New Zealand, an isolated gold mining settlement near Atarauk in Westland’s Grey River Valley. He was one of at least eight children of a Swedish father, Anton Anderson, and an Irish-born mother, Catherine Flaherty. He spent his first years with his family in a two-room shack beside his father’s water-race. After attending the local school, he worked at gold mining with his father in his hometown of Upper Moonlight.[3]

Career as Civil Engineer

In 1914, Anderson and his brother, Fred, immigrated to the United States, where they first worked as surveyors in Hoquiam, Washington. Anton Anderson took his engineer examinations at Seattle University and passed with flying colors. He came to Anchorage in 1916 to work for the Alaskan Engineering Commission (AEC), as one of the resident engineers during the early construction of the Alaska Railroad, surveying and engineering much of the railroad line and the original townsite of Anchorage.[4] He also helped plan and design many of the bridges and buildings between Seward and Fairbanks. Later, it was said of him: “that he at one time knew every tie, curve and grade in the track.”[5]

After completion of the Alaska Railroad in 1923, he apparently went back to New Zealand, and then returned to the United States. He married Alma Florence Menge in Williston, North Dakota on January 1, 1929. Alma Menge was born on August 17, 1899 at Ada, Minnesota. The marriage produced three daughters: Jean (born in 1931, at Klamath Falls, Oregon); Patricia (born in 1933, at Anchorage); and Shelby (born in 1936, at Palmer, Alaska).[6]

About 1929, Anderson returned to Alaska to do tunneling work and to participate in several major projects. He participated in the construction of the Eklutna hydroelectric power project dam. The project began in July 1928, with major units of the project—the dams, tunnel and penstock, power house, and substations. It was not until January 1930 that full-time production began at the complex, which was located forty miles northwest of Anchorage.[7] He also became a road master and undertook several major survey projects to develop the Territory of Alaska, including assignments in the Arctic areas of Alaska and in the Yukon.[8] During the 1930s, he was the location engineer for the sites for the original Matanuska Valley Colonization Project and principal engineer for the U.S. Army in Alaska during World War II. In 1940, he was naturalized as a U.S. citizen at the U.S. District Court at Anchorage.[9]

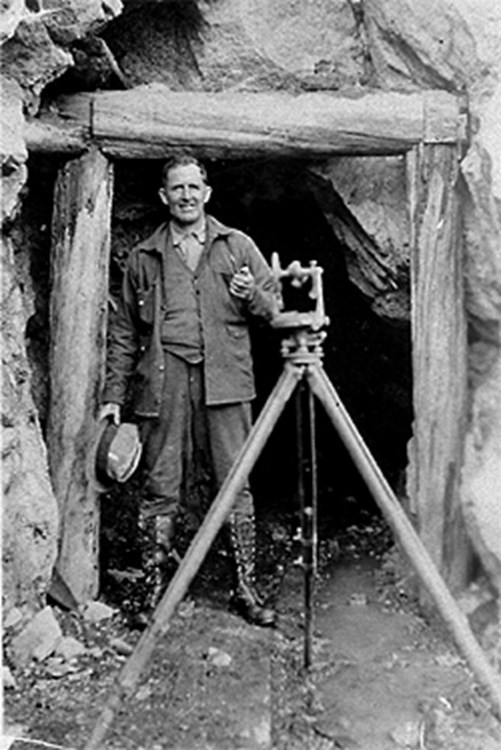

Whittier Tunnel (1941-1942)

Anderson’s crowning achievement was as chief engineer in constructing two tunnels for the Whittier Tunnel project in 1941-1942. In the spring of 1941, survey parties under the direction of Anton Anderson, F.A. Hanson, and Olavi V. Kukkola determined the final locations for the tunnels, railroad, and terminal. In 1941, work was started on two railroad tunnels, the laying of a 14-mile railroad track from Portage to Whittier, and constructing a dock and terminal facility at Whittier. The shorter tunnel (Moraine Tunnel), 4,910 feet long, was on the west side of the project close to the moraine of nearby Portage Glacier. The second tunnel (Whittier Tunnel), 13,090 feet long, had an outlet near the Whittier Glacier. On November 20, 1942, the holing through ceremony of the Whittier tunnel was held and crews finished completely in 1943.

The two tunnels, separated by Bear Valley, provided a railroad linkage between the Army’s port at Whittier to the Alaska Railroad’s line at Portage, south of Anchorage. The rail line cut-off to Whittier shortened the distance from tidewater to Anchorage and Fairbanks by 51.5 miles and avoided the 50-mile mountainous section between Seward and Portage. With the Whittier port in operation, the railroad handled 75 percent more freight traffic than would have been possible through the port of Seward. The $11 million port project, with docks, power plant, rail yards, warehouses, and housing, was completed in 1943. With the rail cutoff in operation, the port of Whittier handled the military traffic; Seward handled the commercial traffic. Nearly 14,000 feet long, the Whittier Tunnel was the largest railroad tunnel in the United States and the fourth largest in the world at the time of its completion.[10]

In the latter months of World War II, Anderson spent time supervising the building of roads and airstrips on Attu Island. He became the assistant chief engineer of the Alaska Railroad at the end of World War II and held this position until his retirement in 1956. He supervised the relocation of the railroad between Potter and Portage when the 128-mile Seward Highway was built along Turnagain Arm, and then opened in ceremonies at Girdwood on October 19, 1951.[11]

The improvement of the Seward Highway was part of a massive six-year road construction program, initially proposed by the U.S. Army in 1947, to develop all-year, all-weather standards of the main routes connecting existing and planned military installations in Alaska. The existence of a road and rail transportation system was essential for its mission of national defense in mainland Alaska to support of its bases and to develop new sources of strategic raw materials. In addition to the Seward Highway, the other main northward and westward routes were the Alaska Highway; the Haines Cut-off; the Richardson and Glenn Highways; and the Tok extension.[12]

Public and Community Service

Anderson was very active in public affairs. He was elected to a one three-year term on the Anchorage City Council (1954-1957). In the October 5, 1954 general municipal election, in a nine-man contest, he polled the highest number of votes, 638, in a record turnout of 1,890 voters representing forty-five percent of an estimated registration of 4,200.[13] He was also chairman of the Public Utilities Commission, and had served earlier as city engineer.

On May 1, 1956, Mayor Ken Hinchey resigned in an effort to “restore harmony” to city government, after a month of conflict with the city council in a long dispute over city contracts. Mel Peterson was temporarily named acting mayor until a new mayor could be selected by the city council.[14] Anton Anderson was elected by unanimous vote by the city council on June 12, 1956 to serve out Hinchey's two-year term.[15] When the next general election was held on October 7, 1957, Anderson was elected to a two-year term as mayor. He was widely credited with using his popularity and tranquil presence to smooth over the city’s relations between various public agencies, namely, the Fairview Public Utility District, and its running battle with the Chugach Electric Association. Anderson was mayor at a time when his mayoral term was shortened when he was forced to resign on November 30, 1958 due to ill health. Hewitt Lounsbury was appointed by the city council to replace him on December 16, 1958.[16] The City of Anchorage proclaimed and organized “Anton Anderson Week” (December 1-7, 1958) in his honor.[17]

Anderson was elected President of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 1951.[18] Alma Antonson was an honored artist and was listed in Who's Who in American Art in 1957.

On March 16, 1960, Anton Anderson died in Mount Vernon, Washington, after several years fighting against Parkinson’s disease.[19] His widow, Alma Anderson, died in 1972. They are both buried in Hoquiam, Washington. They were survived by three daughters, Patricia Anderson, Jean Anderson Graves, and Shelby Anderson.

Legacy

William Dorcy, the manager of the Alaska Railroad, officially named and dedicated the two Whittier tunnels in his honor in 1976. On the door of the tunnel, a bronze plaque, with words telling of his achievement in engineering it through the mountains. Anderson’s granddaughter, Sheila, the daughter of Jean Anderson Graves, unveiled the plaque.[20] He was called "Mr. Alaska Railroad" and often said: "I think I walked over more of Alaska than any man since Alfred Brooks."[21]

In 1976, Robert B. Atwood, in his Anchorage Times newspaper column, “Between Us,” wrote about the dedication ceremony that was attended by a small group of Anderson’s friends in Whittier:

“Ole Kukkola, who served as associate engineer and lived in the same camp at Whittier with Anderson, told the group of the engineering problems that Anderson overcame to make the tunnel project a success. For instance, Anderson computed by triangulation over the top of the mountains the directions to be followed by tunneling crews working toward each other from opposite sides of the mountain. If Anderson had erred, those two crews would have never have met and we may have had two tunnels through the mountain. But he didn’t err. When the two crews met they found their tunnels off only one-half inch in elevation, one-eighth inch in line and one foot in length, which, in engineering language, means no mistake at all.”[22]

The State of Alaska opened a toll road alongside the railroad tracks in 2000, creating North America’s longest combined railroad-highway tunnel, and it was named for him.[23]

Endnotes

[1] See, “Ovation Given Anton Anderson at Chamber Meeting,” Anchorage Daily Times, December 2, 1958, 5; and Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places (Anchorage: Todd Communications, 2008), 8.

[2] Robert B. Atwood, “Between Us,” Anchorage Times, December 19, 1976, A-5.

[3] Neill Atkinson, Mary Patricia Anderson (1887-1966), from the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, Te-Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated October 30, 2012, http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/4a13/anderson-mary-patricia (accessed November 13, 2016); John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 144; and Index card, Anton Albert Anderson, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1788, Indexes to Naturalization Records of the U.S. District Court for the District, Territory, and State of Alaska (Third Division), 1903-1991, Roll 1, U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project), [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed July 10, 2016).

[4] “Coast Born Alaska Railroad Pioneer has Died,” Grey River Argus (Grey River, New Zealand), March 23, 1960, in Anton Anderson file, Bagoy Pioneer Family Files (2004.11), Box 1, Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK; and “Ex-Mayor Anderson Dies in Mt. Vernon,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 17, 1960, 1.

[5] “Mayor is Honored for Years of Service” [Editorial], Anchorage Daily Times, December 2, 1958, 4.

[6] Index card, Anton Albert Anderson, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1788, Indexes to Naturalization Records of the U.S. District Court for the District, Territory, and State of Alaska (Third Division), 1903-1991, Roll 1, U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project), [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed July 10, 2016).

[7] Michael Carberry and Donna Lane, Patterns of the Past: An Inventory of Anchorage’s Historic Resources (Anchorage: Community Planning Department, Municipality of Anchorage, 1986), 123-124.

[8] “Coast Born Alaska Railroad Pioneer has Died,” Grey River Argus (Grey River, New Zealand), March 23, 1960, in Anton Anderson file, Bagoy Pioneer Family Files (2004.11), Box 1, Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK.

[9] Index card, Anton Albert Anderson, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1788, Indexes to Naturalization Records of the U.S. District Court for the District, Territory, and State of Alaska (Third Division), 1903-1991, Roll 1, U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project), [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed July 10, 2016).

[10] For further information on the history of the Whittier Tunnel project, please see these sources: James D. Bush, Jr., Narrative Report of Construction, 1941-1944 (Anchorage: Construction Division, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1944?; reprint ed., Anchorage: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Alaska District, 1984): 122-126 and 375-381; Lisa Mighetto and Carla Homstad, Engineering in the Far North: A History of the U.S. Army Engineer District in Alaska, 1867-1992 (Fort Belvoir, VA: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1997; Helena, MT: History Research Associates, Inc., 1997), 64-68; Lyman L. Woodman, Duty Station Northwest: The U.S. Army in Alaska and Western Canada, 1867-1987, Volume Two, 1918-1945 (Anchorage: Alaska Historical Society, 1997), 142-144; Anton Anderson Memorial Tunnel, Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities, http://tunnel.alaska.gov/history.shtml (accessed November 13, 2016). See also Al-Amin L. Smith, Biographical Note, Guide to the Olavi V. Kukkola Papers, 1941-1964 (HMC-1084), Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, AK.

[11] “Mayor is Honored for Years of Service [Editorial],” Anchorage Daily Times, December 2, 1958. 4; and Claus M.-Naske, Paving Alaska’s Trails: The Work of the Alaska Road Commission, Alaska Historical Commission Studies in History, No. 152 (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1986), 246.

[12] Claus M.-Naske, Paving Alaska’s Trails: The Work of the Alaska Road Commission, 227.

[13] “Elect Anderson, Davis; McLaughlin Easy Winner as Magistrate,” Anchorage Daily Times, October 6, 1954, 1.

[14] “Mayor Ken Hinchey Resigns,” Anchorage Daily Times, May 2, 1956, 1; and “Peterson Not Interested; Acting Mayor won’t take Permanent Post,” Anchorage Daily Times, May 3 1956, 1.

[15] “Anton Anderson Elected Mayor,” Anchorage Daily Times, June 13, 1956, 1.

[16] Municipal Clerk’s Office, Municipality of Anchorage, History of Mayors and Assembly Members [Mayors and Councilmen of the City of Anchorage, Alaska, 1925-1985]; and Municipal Clerk’s Office, Municipality of Anchorage, Honor Roll of Anchorage Mayors, https://www.muni.org/Departments/Assembly/Clerk/Elections/Documents/Honor%20Roll%20of%20Anchorage%20Mayors.pdf (accessed November 13, 2016). See also, “Name Lounsbury Mayor; Yesenski Joins Council,” Anchorage Daily Times, December 15, 1958, 1.

[17] “Ovation Given Anton Anderson at Chamber Meeting,” Anchorage Daily Times, December 2, 1958, 5; and “Mayor is Honored for Years of Service [Editorial],” Anchorage Daily Times, December 2, 1958. 4.

[18] Frank Nyman, “A History Lesson: Engineering in Alaska has come a Long Way,” Alaska Business Monthly, February 1, 2004, 43-45.

[19] “Ex-Mayor Anderson Dies in Mt. Vernon,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 17, 1960, 1; and “Many Honor Anderson,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 18, 1960, 1.

[20] Robert B. Atwood, “Between Us,” Anchorage Times, December 19, 1976, A-5.

[21] Quoted in “Ex-Mayor Anderson Dies in Mt. Vernon,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 17, 1960, 1; reprinted in, John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935, 144. Alfred M. Brooks (1871-1924) was the Alaskan scientist and explorer for whom the Brooks Range is named.

[22] Robert B. Atwood, “Between Us,” Anchorage Daily Times, December 19, 1976, A-5.

[23] Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places, 8.

Sources

This biographical sketch of Anton Anderson is based on an essay which originally appeared in John Bagoy's Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 144-145. See also Anton Anderson file, Bagoy Family Pioneer Files (2004.11), Box 1, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage,AK. Photographs courtesy of the Anderson Family. Edited by Mina Jacobs, 2012. Note: edited, revised, and substantially enlarged by Bruce Parham, November 16, 2016.

Preferred citation: Bruce Parham, “Anderson, Anton A.,” Cook Inlet Historical Society, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, http://www.alaskahistory.org.

Major support for Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, provided by: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Atwood Foundation, Cook Inlet Historical Society, and the Rasmuson Foundation. This educational resource is provided by the Cook Inlet Historical Society, a 501 (c) (3) tax-exempt association. Contact us at the Cook Inlet Historical Society, by mail at Cook Inlet Historical Society, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, 625 C Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 or through the Cook Inlet Historical Society website, www.cookinlethistory.org.