Beaton, John

1875-1945 | Miner and Businessman

John Beaton was the co-discoverer of the Iditarod gold field, the site of one of the last great stampedes or rushes in Alaska. The Iditarod mining district lies between the lower Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers in southwestern Alaska.1 The discovery of gold by Beaton and his partner, W.A. “Bill” Dikeman, on Otter Creek in 1908 made the Iditarod area one of the more important mining areas in Alaska. Their discovery became the third most important placer mining area, only exceeded by Nome and Fairbanks. In 1932, a Seattle Times reporter interviewed Beaton and gave this description of Beaton’s character:

a small, quiet, calm man – you’d never in the world take him for a fellow whose life has been one series after another of wild romantic escapades—is in Seattle today. He has won fortunes and lost them, missed death by minutes, played cards with cut-throats, pistol-on-the-table gamblers, been locked up for winters in frozen wastes, made friends who would die for him, found gold nuggets as big as pea pods, and eaten two tons of beans. 2

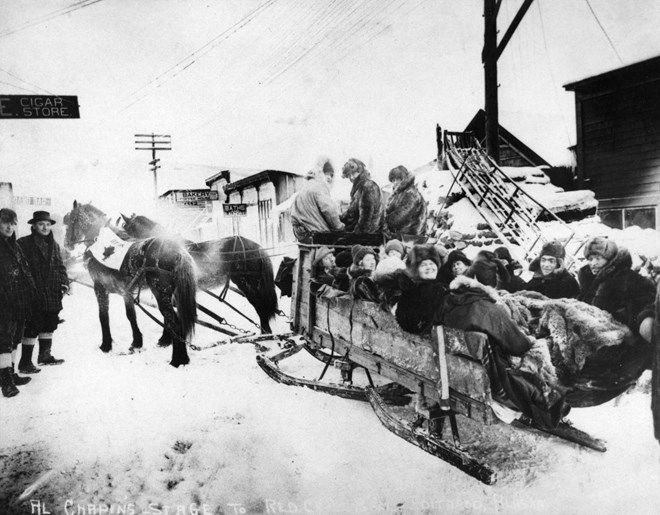

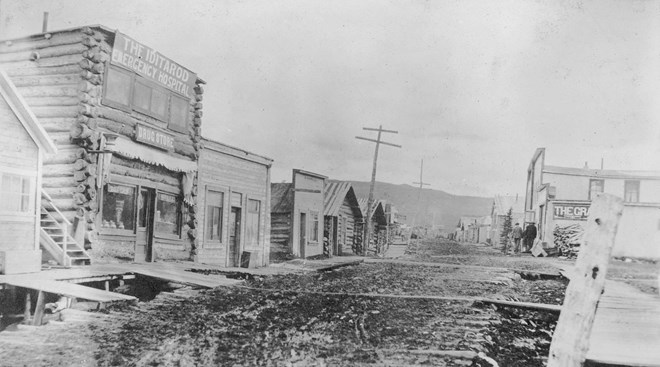

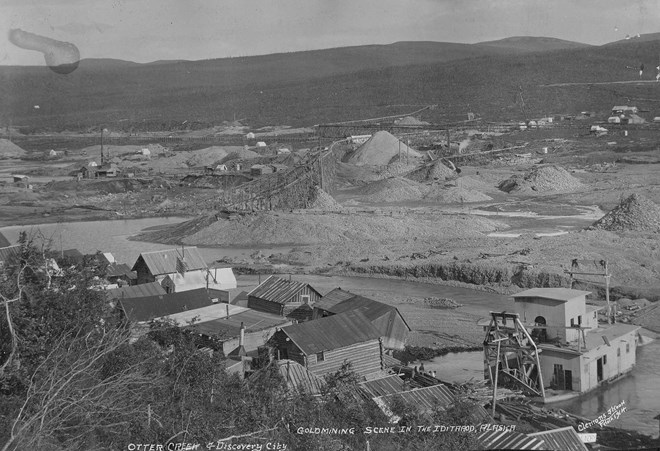

On Christmas Day, 1908, Beaton, William A. Dikeman, both veterans of the Klondike gold rush, and young Murdock Beaton (John’s younger brother) discovered high-grade pay dirt at a depth of twelve feet near the head of Otter Creek in Flat, near the Iditarod River.3 This resulted in the Iditarod gold rush (1908-1910), called Alaska’s last major gold rush, though gold continued to be found in many other areas afterwards. Iditarod was located on a twisting tributary of the Innoko River, and it became a booming mining camp. The Iditarod gold rush was located in what was virtually an unknown region, loosely termed the “Inland Empire”—an area spreading from Ruby on the Yukon River, south along the Kuskokwim Mountains into the drainages of the Innoko and Upper Kuskokwim Rivers.4 The gold rush into Iditarod brought from 4,000 to 10,000 stampeders to the booming mining towns of Iditarod and Ruby. In the next two decades, $30 million in gold was dug from these goldfields. The interior camps at Iditarod and Ruby were isolated; the majority of stampeders used the river system from May to October, traveling 1,000 miles by steamboats up the Yukon, Innoko, or Kuskokwim Rivers. During freeze-up, traffic shifted to trails, which were upgraded by the Alaska Road Commission in an effort to connect military posts and new mining camps with tidewater ports and navigable streams.5

Nova Scotia to Alaska

Beaton was born on August 9, 1875, at Rear Little Judique (later St. Ninian), Inverness, Nova Scotia, the second of six children of Donald Beaton and Anne Mclean Beaton.6 The family, staunch Scot Roman Catholics, came from the Isle of Skye, in Scotland, where John’s grandfather, Angus Beaton, had immigrated to Pictou, Nova Scotia, on the vessel Dove in 1801. The Beaton’s clan name, MacBeth, is as old as any, and the family claimed descent to Macbeth, King of Scotland from 1040 to 1057 A.D. Little is known of Beaton’s early life.

John Beaton’s travels from Canada to Alaska between 1894 and 1908 are uncertain. He appears to have left Nova Scotia for British Columbia in 1899 and shortly thereafter moved to the Klondike. After most opportunities in the Klondike had disappeared, he arrived in Alaska in 1900. He may have worked in the hard rock mines in the Juneau area, but his activities between 1900 and 1908 are largely unknown. The 1910 Alaska Census indicates that he had immigrated to the United States in 1894, but had not filed his “first papers” or declaration of intention to become a U.S. citizen.7

Gold Discovery at Otter Creek and the Iditarod Gold Rush (1908-1910)

In 1908, Beaton partnered with W.A. “Bill” Dikeman and Merton “Mike” Marston to prospect (unsuccessfully) in the Innoko district west of McGrath. Only two of the men, John Beaton and W.A. “Bill” Dikeman, assisted by Beaton’s younger brother, Murdock, prospected in the Iditarod area in the fall of 1908. Marston stayed in town to work any job to order food and supplies for their mining venture.

Beaton and Dikeman purchased a small side-wheel steamer, the K.P.M., built in Fairbanks. Some prospectors had arrived at the Innoko River about the same time with the vessel. Beaton and Dikeman had heard that they were wanted by federal authorities for carrying passengers without a license, so they wanted to get rid of the vessel. They bought the steamer in Holy Cross and headed up the Innoko River, where they beached the boat and built a small log cabin about eight or nine miles below the site of Iditarod.8 According to information supplied by Beaton’s heirs, they were searching for a place deep enough to tie up for the winter. After beaching the boat, they then proceeded south into the mountains and began to prospect. On Christmas Day, 1908, Beaton, Dikeman, and young Murdock Beaton, hit high-grade pay dirt at a depth of twelve feet near the head of Otter Creek.

Beaton, who had a thick “Gaelic” accent according to local historian John Bagoy, proclaimed “Pull ashore; I dit a rod.”9 The others used Beaton’s phrase, Iditarod, to name the place where they built a cabin for the winter and begin to dig. The site was named Discovery. Years later, Beaton remembered it was the twenty-seventh shaft that the two men had sunk or “put down” in the hard-frozen ground at Iditarod that year.10 They had gathered firewood and then set fires to thaw a few inches of ground. After removing the dirt, they would start the process all over again. The labor was slow and backbreaking.11

News of the discovery at Iditarod galvanized Fairbanks and brought prospectors in the summer of 1909, and then a rush of between 4,000 and 10,000 people flooded into the area in 1910 as more gold was found in the neighboring area known as Flat. In no time at all, the Iditarod gold field was being called another “Klondike,” with stampeders coming from elsewhere in Alaska and also from the States. All of Otter Creek became staked, with 660 holes sunk, in different places. All of the holes reaching bedrock showed pay dirt. Other miners worked on a paystreak about a hundred feet wide on Yankee Creek. Coarse gold was found on Ganes and Ophir Creeks.12 The Iditarod Trail was opened in late 1910, connecting the Iditarod region to Cook Inlet and Seward.

Personal Life and Business Career

Soon after the Otter Creek discovery, Beaton traveled to Nova Scotia to marry Florence MacLennan13 or MacLennon14 in Inverness County, near his old home. He returned to Iditarod with Florence, who was reputed to be the first white woman to live in the new mining camp. Other women soon arrived, and the Beatons formed a close friendship with Croatian immigrants John Bagoy and Peter Miscovich and their wives. The Bagoys, like the Beaton family, later moved to Anchorage. Beaton, by all accounts a wealthy man, leased many of his placer claims to other miners and collected royalties.15 With partners from Seattle and Fairbanks he successfully operated a gold dredge in 1916-1917 on Black Creek. He had also invested in dredging equipment.16 By 1918, Beaton had become a naturalized American citizen.17

On October 23, 1918, Beaton’s wife, Florence, and their two young children, six-year old Lauretta and four-year old John Neil, left Skagway on the Canadian Pacific steamer Princess Sophia, which also carried much of the season’s gold. Florence Beaton was taking her son and daughter, who had been born in Alaska, outside for the first time to have their first glimpse of civilization. The Princess Sophia soon struck Vanderbilt Reef in Lynn Canal near Juneau. Other passing ships offered to take the passengers off but the captain decided to wait for the arrival of another Canadian Pacific ship. A storm with one-hundred mile per hour winds smashed and moved the damaged ship off the rocks, and she sank with the loss of all 353 passengers and crew. This was the worst maritime disaster for loss of life in Alaskan waters. Soon after the disaster, the bodies of Florence and Loretta were supposedly found and identified by Gilbert Bates, a business partner of Beaton, who had come up from Seattle to take charge of the bodies. Up until Christmas of that year, the Dawson Daily News noted that neither his son nor his daughter had been found.18 When Beaton himself traveled to Juneau in the third week of December to arrange for funeral services and burial, he found that although the woman previously identified was indeed his wife, he discovered to his horror, the girl was not his daughter, Lauretta. Lauretta’s body was never found.19

After the death of his family, John Beaton purchased a cattle ranch in British Columbia, which he owned until 1927. He also invested in the old Strand Theater in Seattle, which proved a mediocre investment. On one of his trips outside in the early 1920s, Beaton met a young widow, Mary “Mae” McDonald. John and Mae met at a dance in Boston and he soon discovered that she was also a native of Nova Scotia and had grown up near his old home. They were married on February 12, 1924 at St. James Cathedral in Seattle. On February 16, 1925, the couple had a son, whom they named Neil Daniel.

Beaton sold some of his claims in the late 1930s to his dredge manager, Alex Mathieson or Matheson. Matheson apparently told Beaton that the Otter Creek site was played out. In actuality, rich grounds were available on the claim, and Matheson made a fortune.

In the later 1930s, Beaton began dredge mining on Ganes Creek close to where he and Dikeman had made their original strike in 1908. This time he partnered with Arthur A. Shonbeck, a prominent Anchorage merchant, farmer, miner, and air service owner. Beaton had known Shonbeck in 1910 at Flat during the Iditarod gold rush. The Depression seemed not to affect Beaton’s fortunes.

In 1936, the Beatons moved to Anchorage. He joined the Elks Club, where he was sponsored by banker George Mumford and Shonbeck. The Beaton children were sent to school in Seattle.

The Ganes Creek mine was closed during World War II. In June 1945, with Germany defeated and with Japan being pressed back, Beaton and Shonbeck returned to Ganes Creek, possibly to consider how to re-open their mining activities. Both men were riding in a truck when Shonbeck, who was driving, apparently had a fatal heart attack. The truck careened off a bridge abutment into Ganes Creek and the two men, trapped inside the truck, drowned.20

John Beaton is buried in Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery in Anchorage, along with his second wife, Mary "Mae," and adopted daughter, Jean.21

The authors gratefully acknowledge the previous research efforts of Charles C. Hawley, the author of the concise but detailed biography of John Beaton in the Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation, where Beaton was an inductee.

Endnotes

- Charles C. Hawley, biographical sketch for John Beaton (1875-1945), 1; Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation; http://alaskamininghalloffame.org/inductees/beaton.php (accessed October 7, 2015). This biography was originally published in the December 2001 issue of the Alaska Miner.

- “Iditarod Discoverer in Seattle,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, February 2, 1932, 2; reprinted from the Seattle Times, January 17, 1932, http://newspapers.com (accessed October 7, 2015).

- Charles C. Hawley, biographical sketch for John Beaton (1875-1945), 1, Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation.

- Iditarod Trail: Historic Overview; Iditarod Historic Trail Alliance, http://iditarod100.org/HistoricOverview.html (accessed October 7, 2015).

- Robert E. King, “The Iditarod National Historic Trail: Historic Overview,” U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Alaska State Office, Anchorage, http://www.blm.gov/ak/st/en/prog/cultural/ak_history/iditarod_nht_historic_overview.print.html (accessed October 7, 2015); and William R. Hunt, Golden Places: The History of Alaska’s Yukon Mining, Chapter 7: Other Stampedes (Anchorage: National Park Service, Alaska Region, 1990), 6-7; http://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/yuch/golden_places/chap7.htm (accessed October 7, 2015).

- Entry for John Beaton, Canada Births and Baptisms, 1661-1959 database; FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F2WH-QTL (accessed October 7, 2015).

- John Beaton, 1910 Alaska Census, Otter Creek, Otter Recording District, Alaska Territory, Enumeration District 3, stamped page 245, National Archives Microfilm Publication T624, Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910, Roll 1748, 1910 United States Federal Census [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed October 7, 2015).

- Charles C. Hawley, biographical sketch of John Beaton (1875-1945), 2, Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation; Mary J. Barry, Seward, Alaska: A History of the Gateway City, Volume I: Prehistory to 1914 (Anchorage: Mary J. Barry, 1986), 152-153; and John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 370.

- John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 370. It is more likely that the name ‘Iditarod’ had its origin in a Deg Hit’an Athabascan name for the river that has been variously written as ‘Haidilatna’ or ‘Haiditarod.’

- “Iditarod Discoverer in Seattle,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, February 2, 1932, 2, http://newspapers.com (accessed October 7, 2015); and Charles C. Hawley, biographical sketch for John Beaton (1875-1945), 2, Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation.

- “Iditarod Discoverer in Seattle,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, February 2, 1932, 2, http://newspapers.com (accessed October 7, 2015).

- Mary J. Barry, Seward, Alaska: A History of the Gateway City, Volume I: Prehistory to 1914, 152-153.

- Charles C. Hawley, biographical sketch of John Beaton (1875-1945), 3, Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation.

- Baptismal record, Anna Flora Maclennon, St. Margaret of Scotland, Broad Cove, Inverness, Nova Scotia, Canada, Antigonish Catholic Diocese, April 21, 1888, 97, Nova Scotia, Antigonish Catholic Diocese, 1823-1905 [database with images], https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JV9L-17S (accessed October 7, 2015).

- Ken Coates and Bill Morrison, The Sinking of the Princess Sophia: Taking the North Down with Her (Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 1991), 19.

- Ibid.

- Draft Registration Card for John Beaton, Local Board No. 18, Iditarod, Fourth Division, Alaska, October 24, 1918, National Archives Microfilm Publication M1509, World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Roll AK-2, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918 [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed October 7, 2015).

- Since the Dawson Daily News and other newspapers did not follow through with the story of the sinking of the Princess Sophia, Ken Coates and Bill Morrison note that it cannot be determined whether the Beatons' children were ever found. See, The Sinking of the Princess Sophia: Taking the North Down with Her, 133, and endnote no. 37, page 207.

- Charles C. Hawley, biographical sketch for John Beaton (1875-1945), 4, Alaska Mining Hall of Fame Foundation; and Ken Coates and Bill Morrison, The Sinking of the Princess Sophia: Taking the North Down with Her, 19 and 133.

- “Two Anchorage Men Drowned at Ophir,” Anchorage Daily Times, June 21, 1945, 1.

- John Beaton, Find-a-Grave Memorial, www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=14671105 (accessed October 7, 2015).

Sources

This essay originally appeared in John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 370-372. See also the John Beaton file, Bagoy Family Pioneer Files (2004.11), Box 1, Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK. Note: edited, revised, and substantially expanded by Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, May 5, 2016.

Preferred citation: Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, "Beaton, John," Cook Inlet Historical Society, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, http://www.alaskahistory.org.

Major support for Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, provided by: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Atwood Foundation, Cook Inlet Historical Society, and the Rasmuson Foundation. This educational resource is provided by the Cook Inlet Historical Society, a 501 (c) (3) tax-exempt association. Contact us at the Cook Inlet Historical Society, by mail at Cook Inlet Historical Society, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, 625 C Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 or through the Cook Inlet Historical Society website, www.cookinlethistory.org.