Delaney, James J., Sr.

1896-1970 | Mayor of Anchorage, and Alaska Railroad administrator

James J. Delaney Sr. worked for a total of forty-one years, the longest period of employment for any of the railroad’s employees. After his death in 1970, “the Park Strip," the fourteen blocks between 9th and 10th Avenues and A and P Streets situated in downtown Anchorage, was officially named as Delaney Park in honor of James J. Delaney, who was Mayor of Anchorage from 1929 to 1932.1

Delaney was fondly remembered, long after leaving office, for capably and gracefully guiding Anchorage through the Great Depression. Delaney used his calm demeanor and steady influence to bring about cooperation between the City of Anchorage, Alaska Railroad, and the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce. He did a good deal to keep people talking and working together on community problems.2

Early Years

James J. Delaney was born in Castlerea, County Roscommon, Ireland, on August 26, 1896. He immigrated to the United States at the age of eighteen, settling in Holyoke, Massachusetts, in 1914.3

He came to Anchorage in 1916, like many others, to work for the Alaskan Engineering Commission, precursor of the Alaska Railroad. He was employed by the railroad for forty-one years in many different positions--clerk (1916-1929), chief clerk (1929-1933), examiner of accounts (1937-1942), assistant general manager (1943-1948), and real estate and contracting agent (1949-1957).4 He retired in 1957 as the Railroad’s real estate and contracting agent.

In 1918, Delaney entered military service during World War I, remaining at Camp Lewis, Washington, near Tacoma, for a short period.5 Although the details of his service are not known, he was probably a private in the Ninety-First Division, known as the “Wild West Division,” as troops came from the western states and Alaska. Army enlistees at the camp seriously trained in anticipation of possible service in Europe.6 Delaney became a naturalized American citizen in January 1919 after his military petition for naturalization, filed at the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington at Tacoma, was approved.7

By 1920, Delaney had returned to Anchorage and resumed his job as a clerk for the Alaskan Engineering Commission.8 Delaney was active within the Anchorage community. He joined the Elks Lodge in 1919 and, in 1924, before he was thirty years old, he became the exalted ruler. He was a member of Jack Henry Post No. 1 of the American Legion.

Mayor of Anchorage (1929-1932)

The economy for Anchorage and the rest of the nation became uncertain in October 1929 when the stock market collapsed, and additional domestic and international complications led to the Great Depression. The local economy was stagnant and primarily dependent on the Alaska Railroad for employment. About one-third of the town’s adults were unemployed. Anchorage’s population, listed at less than 1,900 at the time of the 1920 federal census, had slowly increased to closer to 2,200 by the time of Delaney’s first term. Delaney was mayor during an economically difficult three-year period, but his record during that time was excellent.9

In April 1929, Anchorage was less than fifteen years old. The hope that the Alaska Railroad would cause widespread development of Alaska’s resources had not been realized. In 1929, the Alaska Railroad had operating revenues of $1,165,910 and operating expenses of $2,090,212. In the words of historian William H. Wilson, “the railroad spent about two dollars to earn each dollar.” In the early 1930s, the Alaska Railroad was still operating at a monthly deficit of $100,000 per month.

In 1929, Delaney was elected to his first term as mayor of Anchorage, receiving 425 votes to the 230 of his opponent, R.C. Loudermilch, a local mortician, auto garage owner, and city council member.10 Delaney was re-elected mayor twice, serving three consecutive one-year terms, between 1929 and 1932. During the last two elections he ran unopposed. In 1930, Hiram W. Mitchell filed a petition at the last minute to enter the race, but it was later withdrawn.11 According to historian Stephen Haycox, Delaney did not want to run for the third term in 1931, and ran only because no one else wanted the position.12

As mayor, Delaney was in the awkward situation of representing the people of Anchorage at a time when there was active discontent and unhappiness in the workforce of the Alaska Railroad and in the business community against Colonel Otto F. Ohlson, the General Manager of the Alaska Railroad, and the mayor’s boss. It was particularly useful at this time to have a mayor who worked for the railroad, as relations between the city and the railroad were often strained. The city relied on the railroad for services, including hospital care and electrical power.13 In 1931, Ohlson had responded to the demands of a Congressional investigative committee,14 chaired by U.S. Senator Robert B. Howell of Nebraska, to cut the Alaska Railroad’s annual deficit by steeply raising cargo and passenger rates and sharply reducing staff. This move was deeply unpopular throughout the railbelt.15

Anchorage’s early history is closely linked with the Alaska Railroad. When Anchorage was a railroad construction camp, electrical service was initiated by the Alaskan Engineering Commission in 1916. The electrical and telephone transmission systems were operated under a lease agreement, first with the AEC and then the Alaska Railroad.16

Delaney, as had previous other mayors, asked the Alaska Railroad to sell the electric and telephone transmission system to the city.17 Previous requests had been unsuccessful. Colonel Ohlson responded in a more positive manner, and steps were taken to set a price and, in Delaney’s second term, tax rates were raised in anticipation of the sale.18 Toward the end of Delaney’s third term, a price of $27,979 had been established and Ohlson had forwarded the proposal to the U.S. Department of the Interior for approval. The city council put an appropriate proposition on the ballot for the April 5, 1932 election. Just prior to the election, Ohlson sent a letter saying that the sale was off. The proposition to approve the purchase of the electric and telephone transmission system remained on the ballot and passed resoundingly, 501 to 51. At their April 11, 1932 meeting, the city council voted to send a letter of complaint about the non-sale to Senator Howell, the longtime critic of the Alaska Railroad and fiscal hawk, who criticized many aspects of the railroad’s operations, including electrical power.19 The lease agreement ended later that year, when the city bought the electrical distribution system for $11,351.20

Besides the Alaska Railroad, Delaney forged effective relationships with the city’s delegation to the Territorial legislature. One member of the city council, H.H. McCutcheon, also was elected to the House of Representatives. The town’s lone senator, Robert Bragaw, was an officer in the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce, which performed the functions of a city and economic development department.21

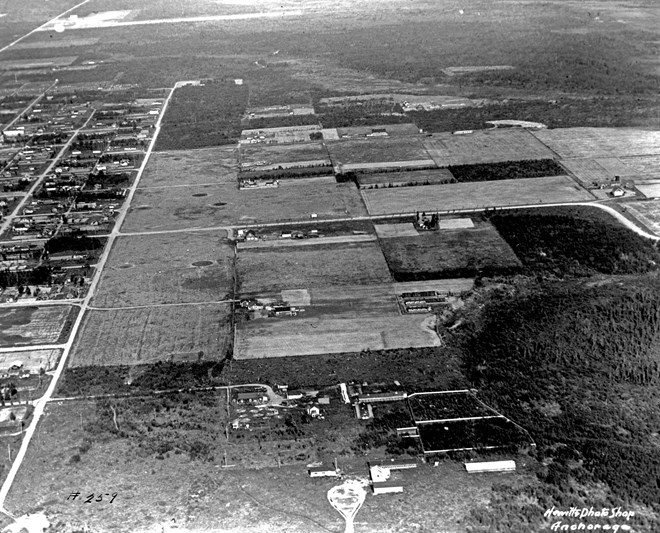

Another major step forward was the development of a new municipal airfield to replace the city’s first landing strip, commonly known as “the Park Strip.” The Park Strip stretches along the south side of Ninth Avenue, between A and P Streets, in downtown Anchorage. The Park Strip was first cleared as a fire break between Anchorage and the surrounding woods. From about 1923 to 1930, it was used as Anchorage’s first aircraft landing strip runway and a golf course until Merrill Field was constructed in 1930.22

The new municipal airfield, Merrill Field, was laid out on a one-hundred-eight acre site, east of town and outside of the city limits, in the Fourth Addition. The city purchased the portions of two homesteads and the remaining land was released for airport use by President Herbert Hoover in 1932.23 On June 5, 1929 Delaney signed a resolution from the Anchorage City Council requesting the new airfield site from the U.S. General Land Office. On July 17, 1929, the city council let a contract to begin clearing the land that was to become Merrill Field. On August 21, 1929, it was announced at the city council meeting that the field was mostly plowed and cleared.24 In early spring 1930, the city council sent a request to the Alaska Road Commission to flatten the new airfield.25 The new airfield was apparently operational by the spring of 1931. On May 1, 1931, the city council informed Alaskan Airways to discontinue using the old runway (the park strip).26

In the spring of 1930, the Anchorage Woman’s Club and the Jack Henry Post of the American Legion requested that the new airfield be named after Russel "Russ" Hyde Merrill (1894-1929), an early Anchorage commercial aviator who had lost his life the year before on a flight to the Bethel area.27 In April 1932, the Anchorage Woman’s Club provided funds to erect a fifty-foot tower and beacon light.28

Anchorage High School was built in 1930, during Delaney’s first term,29 on the south side of the school reserve.30 The city issued $65,000 in bonds to pay for its construction.31 In the previous two bond elections before Delaney assumed office, voters had turned down issues of $125,000 and $100,000.32 According to historian Stephen Haycox, Delaney arranged for C.H. Holmes, an assistant manager at the Alaska Railroad, to perform the necessary engineering study and building inspection on the new school. Holmes performed this work, without pay, as the city had no certified building inspector.33

The Anchorage City Council dealt with numerous mundane matters. The contentious “dog question” and what to do about stray dogs repeatedly came up.34 The city council approved oiling some of the main streets to reduce dust, after soliciting the opinions of the Fourth Avenue merchants.35 An ordinance governing the operation of the Anchorage Memorial Cemetery was passed.36 Some homeowners were still using backyard privies along streets where sewer lines were laid to connect to the sewer system. The Police Department had to step in by requiring them to remove the privies and to fill in the privy holes.37 The Radio Committee of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce requested that the city adopt an ordinance banning interference with radio signals, specifically the fledgling radio station KFQD.38

On November 5, 1931, four prominent Anchorage women (Mrs. J.B. Gottstein, Mrs. E.L. Winterberger, Mrs. George E. Mumford, and Mrs. Fred Schodde) representing the “mothers of Anchorage” appeared before the city council, demanding a public health ordinance be passed. Specifically, they sought the establishment of a board of health, the hiring of a public health officer, and passage of strict quarantine laws. There were cases of mumps and measles among Anchorage children, and scarlet fever and whooping cough were known from other parts of the Territory. The council responded by authorizing the hiring of a health officer for sixty days and then passed Ordinance 84, covering public health, on February 17, 1932.39 Dr. J.H. Romig was hired as the public health officer.40

Personal Life

In 1929, Delaney married Nancy Marie Dillon, an Irish immigrant, who was born in Aghamore, County Mayo, Ireland, on March 5, 1896. She immigrated to America in 1927. They had three children, Nancy, James, Jr., and Loretta. The couple established a home at 303 K Street, where the Boney Memorial Court now stands. Delaney was very proud of the three flowering crabapple trees at his home in downtown Anchorage. A single cutting from one of his trees grew into the crabapple tree that still flourishes in the courthouse parking lot. After his third term as mayor ended in 1933, Delaney was appointed as chair of the town’s parks committee.

Delaney died on April 20, 1970, at the age of seventy-three, at Providence Hospital in Anchorage.41 His widow, Nancy Delaney, died in Anchorage on December 29, 1986. The couple is buried in the Catholic Tract of Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery.

Delaney is remembered today through the Delaney Park Strip, the long, narrow green space between 9th and 10th Avenues, immediately south of Anchorage’s downtown. Officially known as Delaney Park, the Park Strip is used year-round for a variety of community events, sports, and festivals. Delaney Street on Government Hill was named in his honor; nearby are other streets in the neighborhood that were named after executives with the Alaska Railroad.42

Endnotes

- Michael Carberry and Donna Lane, Patterns of the Past: An Inventory of Anchorage’s Historic Resources (Anchorage: Community Planning Department, 1986), 194; and Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places (Anchorage: Todd Communications, 2008), 26-27.

- Stephen Haycox, “Delaney Gracefully Guided Anchorage through Depression,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 8, 1987, B-1; and John P. Bagoy, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 127.

- James Joseph Delaney, Military Petition and Record for Naturalization, No. 6208-M, January 27, 1919, U.S. District Court, Western District of Washington, Southern Division (Tacoma), National Archives Microfilm Publication M1542, Naturalization Records for the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington, 1890-1957, Roll 134, U.S., Naturalization Records-Original Documents, 1795-1972 (World Archives Project), [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed September 15, 2015).

- James J. Delaney, Official Register of the United States: Persons Occupying Administrative and Supervisory Positions in the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial Branches of the Federal Government, and in the District of Columbia, Volume 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1929-1933, 1937-1947, and 1949, U.S., Register of Civil, Military, and Naval Services, 1863-1959 [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed September 15, 2015).

- James Joseph Delaney, Military Petition and Record for Naturalization, January 27, 1919.

- Duane Colt Denfeld, “Fort Lewis, Part I, 1917-1927,” HistoryLink File #8455, HistoryLink.org: The Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History, http://historylink.org (accessed September 16, 2015).

- James Joseph Delaney, Military Petition and Record for Naturalization, No. 6208-M, January 27, 1919.

- James J. Delaney, 1920 U.S. Census, Anchorage, Knik Recorder's District, Third Judicial District, ED 11, page 24A, National Archives Microfilm Publication T625, Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920, Roll 2031, United States 1920 Federal Census [database on-line], http://ancestry.com (accessed January 8, 2015).

- Stephen Haycox, “Delaney Gracefully guided Anchorage through Depression,” Anchorage Times, March 8, 1987, B-1; and Evangeline Atwood, Anchorage: All-America City (Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1957), 25.

- “J.J. Delaney Wins Place as Mayor of Anchorage in Lively City Election,” Anchorage Daily Times, April 2, 1929, 1.

- “Four Candidates Enter City Race; Two Tickets Now,” Anchorage Daily Times, March 22, 1930, 8; and “Gill and Carlson are Re-Elected by Voters; Tarwater Wins Place,” Anchorage Daily Times, April 2, 1930, 1.

- Stephen Haycox, “Delaney Gracefully guided Anchorage through Depression,” Anchorage Times, March 8, 1987, B-1.

- Ibid.

- The official name of this committee was the “Special Select Committee on Investigation of The Alaska Railroad.” The other members were Senators John B. Kendrick of Wyoming and John Thomas of Idaho, Chairman Frank McManamy of the Interstate Commerce Commission, and an I.C.C. examiner whose job was to review the railroad’s accounts. William H. Wilson, Railroad in the Clouds: The Alaska Railroad in the Age of Steam, 1914-1945, 198-199.

- Ibid., 50, 199 and 202-203.

- Michael Carberry and Donna Lane, Patterns of the Past: An Inventory of Anchorage’s Historic Resources, 106-107 and 123-124.

- Minutes, May 1, 1929, Anchorage City Council Minutes, Volumes I and II, November 26, 1920-May 27, 1933 (microfilm edition), Alaska Collection, Z.J. Loussac Library, Anchorage Public Library, Anchorage, AK.

- Minutes, November 11, 1931, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, April 11, 1932, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- “History,” Municipal Light & Power,” 3, https://www.mlandp.com/redesign/about_mlp.htm (accessed September 19, 2015).

- Stephen Haycox, “Delaney Gracefully Guided Anchorage through Depression,” Anchorage Times, March 8, 1987, B-1.

- Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places, 26-27; and Michael Carberry and Donna Lane, Patterns of the Past: An Inventory of Anchorage’s Historic Resources, 195.

- Ibid., 194-195.

- Minutes, June 5, July 17, and August 21, 1929, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, April 16, 1930, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, February 4, 1931, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, April 2 and May 7, 1930, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, November 5, 1931, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Claus-M. Naske and L.J. Rowinski, Anchorage: A Pictorial History (Norfolk, VA: Donning Company, Publishers, 1981), 116.

- The school reserve was located between Fifth and Sixth Streets and F and G Streets on the 1915 townsite plat. See reproduction of “Plat of Anchorage Townsite, 1915,” in Fond Memories of Anchorage Pioneers, Volume II (Anchorage: Pioneers of Alaska, Igloo 15, Auxiliary 4, 2003), 6-7.

- Minutes, June 19, 1929 and February 19, 1930, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- “Former Mayor J.J. Delaney has Lived Here 49 Years,” Anchorage Daily Times, July 10, 1962, 6.

- Haycox, “Delaney Gracefully guided Anchorage through Depression,” Anchorage Times, March 8, 1987, B-1; and Minutes, March 4, 1931, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, May 1, 1929, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, May 1, 8, and 15, 1929, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, July 3, 1929, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, September 19, 1929, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, March 19, 1930, Anchorage City Council Minutes; and Carl Martin to the Anchorage City Council, July 22, 1931, attachment, Minutes, September 2, 1931.

- Minutes, November 5, 1931 and February 17, 1932, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- Minutes, March 2, 1932, Anchorage City Council Minutes.

- “Former Mayor James Delaney Dies in Hospital,” Anchorage Daily Times, April 20, 1970, 2.

- Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places, 26-27.

Sources

This entry for James J. Delaney Sr. originally appeared in John Bagoy’s Legends and Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 127. See also the James Delaney file, Bagoy Family Pioneer Files, Box 3, Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK. Note: updated and revised by Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, September 7, 2015.

Preferred citation: Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, “Delaney, James J., Sr.,” Cook Inlet Historical Society, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, http://www.alaskahistory.org.

Major support for Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, provided by: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Atwood Foundation, Cook Inlet Historical Society, and the Rasmuson Foundation. This educational resource is provided by the Cook Inlet Historical Society, a 501 (c) (3) tax-exempt association. Contact us at the Cook Inlet Historical Society, by mail at Cook Inlet Historical Society, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, 625 C Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 or through the Cook Inlet Historical Society website, www.cookinlethistory.org.