Shonbeck, Arthur A. "Art" or "A.A."

1878-1945 | Gold Miner, Businessman, and Civic Leader

Arthur A. Shonbeck has been called “a man of action.” In Anchorage’s early years, Shonbeck was recognized as one of the city’s best business owners. He established a retail, wholesale, and outfitting business (Shonbeck General Merchandise) as Anchorage grew and prospered. He later became a director of Alaska’s largest bank – the National Bank of Alaska. Shonbeck was also a mining promoter who provided “services, equipment, transportation, financing, and hands-on mining experience to Alaska’s mining industry” and was also a miner owner and operator.1 He was a dedicated civic leader, politician, and a founder of the first locally owned air transport company.

Evangeline Atwood, in Anchorage: All-America City (1957), placed Shonbeck the first among the sixteen individuals who "weathered the early storms which determined the town's destiny." He was one of the “courageous men and women” who came to Anchorage as pioneers, stayed, and called it home. He was one of the dedicated persons who “kept Anchorage alive” when it was in danger of becoming a ghost town three years after it was established in 1915. Such individuals as Shonbeck “envisioned a bright new future for the Territory.”2

Wisconsin to Alaska

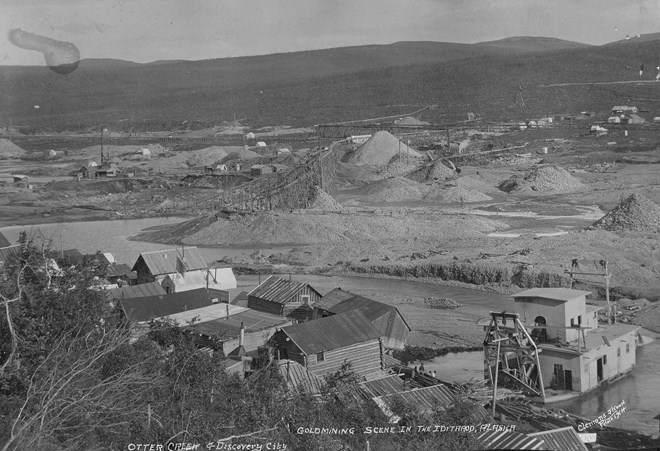

Arthur "Art" Arnold Shonbeck (sometimes known as ‘Double A’) was born in Clayton, Wisconsin on August 8, 1878. He stampeded to Alaska, at the age of twenty-two, during the Nome gold rush, arriving in Nome on June 18, 1900.3 When the sizeable Tanana Valley rush developed in the Fairbanks area in 1902, he moved there. He operated a short-lived retail store in Chatanika named Courtney and Shonbeck. He sold his interests and moved to Seattle, but returned to Fairbanks in 1906 as it was beginning to boom. In 1903, Shonbeck married Anna Peckinpaugh (also known as "Ann" or "Anne"). He was in Cleary the following year, working as a salesman for R.H. Miller and Company.4 In 1910, he went to Iditarod when news came of the discovery of gold and made a small fortune. At Flat, a few miles from Iditarod, he opened a store to sell merchandise to the mining community.5

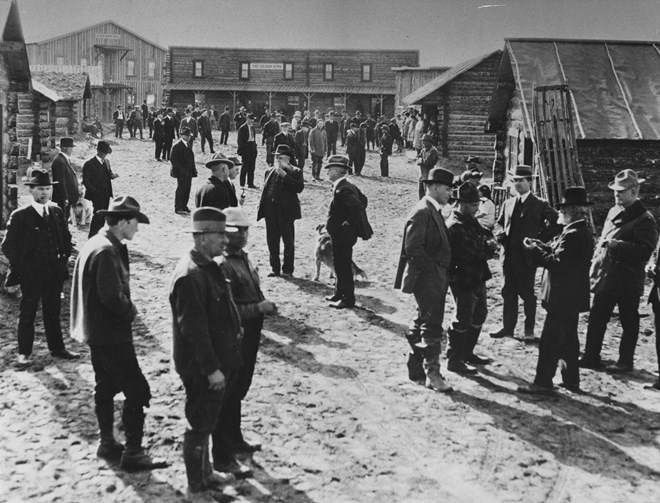

Anchorage

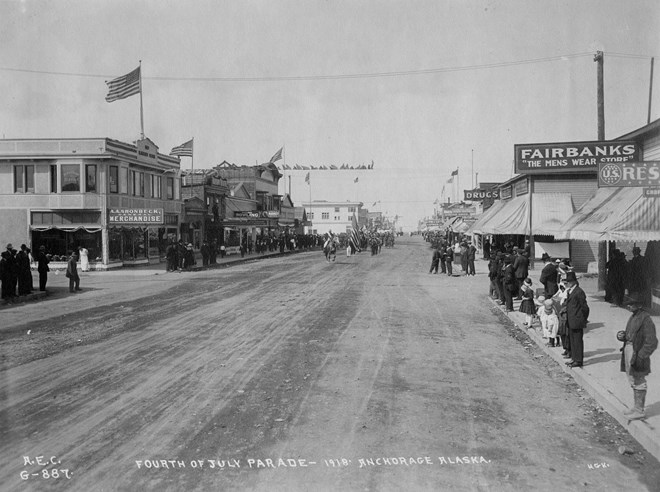

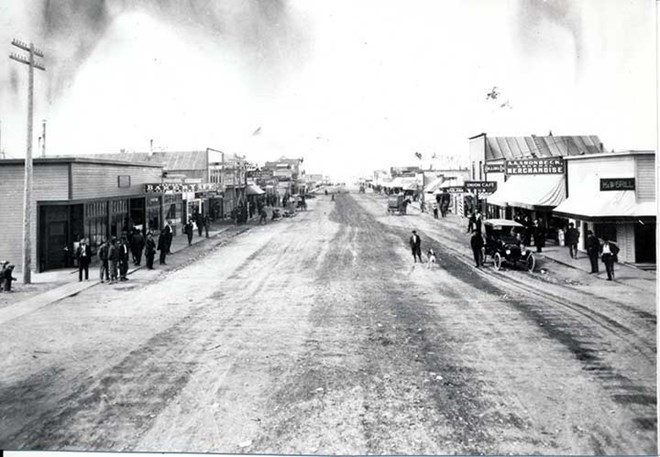

In 1915, Anchorage was selected as the construction headquarters for the Alaska Railroad. By midsummer a substantial tent city had sprung up at the mouth of Ship Creek with a population of several thousand people.6 Entrepreneurs like Arthur Shonbeck flocked to the construction headquarters, anticipating that a substantial community would grow up around the railroad headquarters. Shonbeck went to Anchorage, in 1915, to seek his fortune with many other boomers. He started with a grocery store. He then became involved with many other business ventures, starting with Shonbeck General Merchandise, a dealer in heavy construction equipment, farm equipment, and airplane parts, located on Fourth Avenue. He was the agent for Standard Oil Company in the Anchorage area. He was the dealer for Ford automobiles and Caterpillar heavy construction equipment, and ran an automobile repair garage. He was a dealer for Giant Powder Company, which sold explosives for miners.

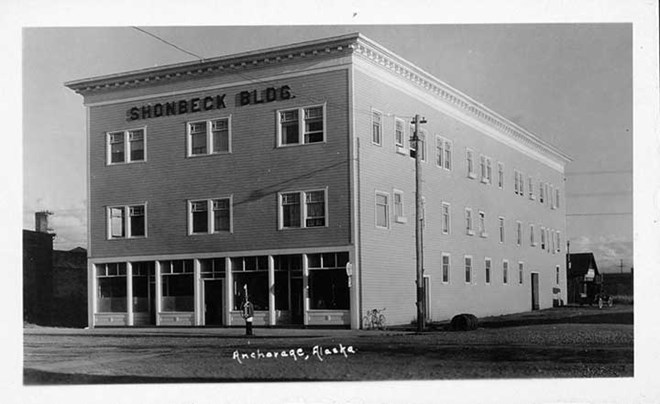

In 1916, Shonbeck built the Bank of Alaska branch building in Anchorage, and was an early if not the first depositor. He later became a director of the bank and a close friend of its owner, Edward A. Rasmuson. In 1920, he purchased the burned-out site of the former Anchorage Labor Temple at 4th and H Street. He built a three-story building, with the top two floors as apartments, known as the Shonbeck Apartments, and the first floor fitted out for retail businesses. When the apartments were ready for occupancy in late summer 1922 there were thirty-two apartments or rooms, fourteen with bathtubs of their own.7 In 1927 he and other prominent Anchorage businessmen formed the Anchorage Times Publishing Company, which produced the Anchorage Daily Times.

Shonbeck retained his early interest in mining throughout his life. In 1920 Shonbeck and several other prominent Anchorage businessmen backed the Evan Jones Coal Mine at Wishbone Hill east of Palmer, which supplied coal to Anchorage. He partnered with Wesley Earl Dunkle and his close friend John Beaton on various mining projects. He had interests in or was a major supplier for the Golden Zone Mine, the Golden Horn project in the Iditarod mining district, and the Flat and Slippery Creek gold mining projects. He owned a placer mine at Ganes Creek near Ophir.

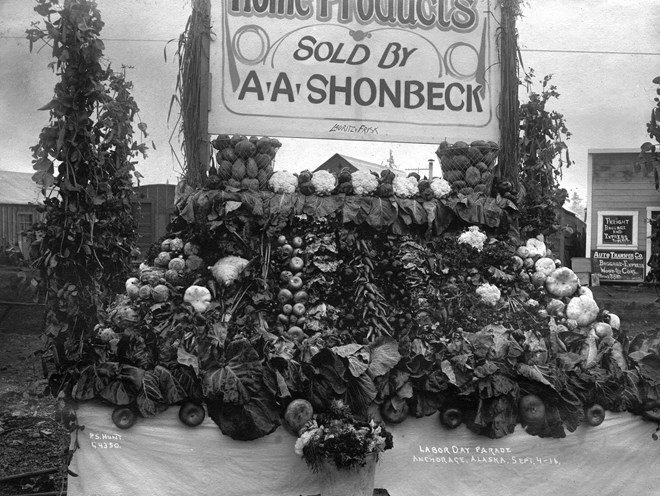

Shonbeck owned and operated one of the largest farms in the Matanuska Valley, raising grains to feed cattle and horses. He also took great pride in experimenting with a variety of fruits and vegetables. Shonbeck also helped to lay the groundwork for the establishment of the Matanuska Valley Colony in 1935.8

Shonbeck was an early aviation enthusiast and could be considered as the “father” of Anchorage’s airline industry. He was a leader in predicting the city’s potential as an air center.9 The year after the first airplane flew in Anchorage, in 1923, Shonbeck organized a group of citizens to clear “the park strip” between Ninth and Tenth Avenues of trees and stumps in case a pilot might want to land in Anchorage.10 He was the president, general manager, and a financial investor in Anchorage Air Transport, Inc., the first local airline company, which was founded on December 29, 1926. The company owned two airplanes, the Travel Air 7000, Anchorage No. 1, and the Travel Air 4000, Anchorage No. 2. Russel Merrill was the first pilot. The company foundered after Merrill disappeared on a flight over Cook Inlet on September 16, 1929 while on a supply run to the New York-Alaska Company’s placer mine at Nyac, near Bethel.11 Around 1932, Shonbeck was backing aviation again, becoming a business partner and a director with Wesley Earl Dunkle’s Star Airlines. Star Airlines later merged with McGee Airlines and, after other mergers, became Alaska Airlines.12

Shonbeck was a dedicated civic leader and political power in Alaska Territory. He served two separate terms on the Anchorage City Council. He was first elected to one term in 1923-1924. He served the second term on the city council, 1932-1933.

In the April 1924 election for mayor of Anchorage, Shonbeck lost by four votes against the incumbent, Michael Joseph Conroy. Nearly a thousand people voted in the election in a town with about two thousand inhabitants. The city council voted Shonbeck back on to finish his unexpired term. When Conroy resigned in November 1924, Councilman Charles Bush nominated Shonbeck to become mayor. Bush favored Shonbeck because he had been a senior member of the council, received the highest number of votes as a councilman, and was “one of the largest taxpayers in Anchorage.” Shonbeck declined the nomination.

Shonbeck was a loyal Democrat. He served as chairman of the Third Division Democratic National Committeeman for Alaska for years. In 1932, after the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt as president, he was mentioned as a candidate for territorial governor, when John Troy, a Juneau newspaperman, was appointed. Shonbeck was chairman of the territorial Democratic central committee from 1934 to 1937.

By the 1930s, Shonbeck was a mover and shaker in Anchorage. Shonbeck’s business interests were so well known that his advertisement in the Anchorage Daily Times was “a bordered space that said ‘A.A. Shonbeck’.”13 Among his friends were Anchorage-Seattle equipment dealer and placer miner Glenn Carrington, attorney Warren Cuddy, Alex McDonald (the agent of Alaska Steam), banker E.R. Tarwater and, of course, mining engineer and airline pioneer Welsey Earl Dunkle.

Shonbeck was a charter member of the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce, and was president in 1922. He was deeply involved with the Western Alaska Fair, which was sponsored by the Anchorage Chamber of Commerce and the Anchorage Woman’s Club between 1924 and 1930.14

In 1925, Republican Governor George Parks appointed Shonbeck to the Board of Regents of the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines (renamed as the University of Alaska in 1935). He was reappointed by Governor Troy in 1933. Due to the press of business, he resigned in 1936.15

Later Years

In the late 1930s, Shonbeck built a house at 1006 G Street, with a detached garage. In Patterns of the Past: An Inventory of Anchorage's Historic Resources (1986), Michael Carberry and Donna Lane give this description:

"Although there are other comfortable homes in the surrounding blocks, this particular house is a remarkably good example of American housing of the prewar era. . . . The tan asbestos shingles of the exterior are complemented by the brown shingle roof. The one and one-half story building is capped with dormer windows. The entrance way, a decreasing series of arches, is formed in concrete. A detached garage, indicative of the role that the automobile would play in daily life, is finished in similar material to the house."[16]

One of Shonbeck’s last contributions to the Anchorage community was his substantial civic support for Providence Hospital in 1939. Led by Harry Hill, he joined a select committee of prominent citizens who supported the hospital’s construction. Anna Shonbeck, his wife, was one of dozens of Anchorage women who founded the hospital’s Auxiliary and raised funds for furnishing the nursery.

On June 21, 1945, Shonbeck and his long-time friend and business partner John Beaton were at Ganes Creek in the Innoko mining district visiting their placer mine. Shonbeck had a fatal heart attack while driving their truck across a bridge abutment and slid into Ganes Creek. The two men were locked inside the cab and drowned.[17]

Arthur Shonbeck’s wife, Anna, moved to San Jose, California in 1947 and died in Pasadena in 1964.[18] They are both buried in the Elks Tract in the Anchorage Memorial Park Cemetery.

Endnotes

- Charles C. Hawley, “Arthur A. Shonbeck (1878-1945),” Alaska Mining Hall of Fame, 1, http://alaskamininghalloffame.org/inductees/shonbeck.php (accessed October 1, 2014). See also, Terrence Cole and Elmer E. Rasmuson, Banking on Alaska: The Story of The National Bank of Alaska, Volume 1: A History of NBA (Anchorage: National Bank of Alaska, 2000), 51.

- Evangeline Atwood, Anchorage: All-America City (Portland, OR: Binfords & Mort, 1957), v-vi. See also, Charles C. Hawley, "Arthur A. Shonbeck (1878-1945),”Alaska Mining Hall of Fame, 6.

- “Shonbeck Rites Are Set For Next Saturday,” Anchorage Daily Times, June 22, 1945, 1 and 8; and Charles C. Hawley, “Arthur A. Shonbeck (1878-1945),” Alaska Mining Hall of Fame.

- Entry for Arthur A. Shonbeck, in David A. Hales, Margaret N. Heath, and Gretchen L. Lake, An Index to Dawson City, Yukon Territory and Alaska Directory and Gazetteer, Alaska-Yukon Directory and Gazetteer, and Polk’s Alaska-Yukon Gazetteer and Business Directory, 1901-1902, Volume VI: P-S (Fairbanks: Alaska & Polar Regions Department, Elmer E. Rasmuson Library, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1995), 64.

- Biographical sketch, Arthur A. Shonbeck,” UA Journey, https://www.alaska.edu/uajourney/regents/1925-1936-arthur-shonbeck (accessed February 3, 2015).

- Stephen Haycox, Alaska: An American Colony (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002), 233-234.

- “Shonbeck Apartments Now Ready for Occupancy," Anchorage Daily Times, August 31, 1932, 1.

- Evangeline Atwood, Anchorage, Star of the North (Tulsa, OK: Continental Heritage Press, 1982), 78.

- Michael Carberry and Donna Lane, Patterns of the Past: An Inventory of Anchorage’s Historic Resources (Anchorage: Community Planning Department, Municipality of Anchorage, 1986), 21.

- See, “Arthur A. Shonbeck," UA Journey. Today, Delaney Park, commonly called “the Park Strip,” was first cleared in 1917 as a fire break between Anchorage and the surrounding woods. It served as a landing strip from 1923 to 1930, until Merrill Field was constructed. Rae Arno, Anchorage Place Names: The Who and Why of Streets, Parks, and Places (Anchorage: Todd Communications, 2008), 27.

- Robert W. Stevens, Alaskan Aviation History, Volume 1: 1897-1928 (Des Moines, WA: Polynyas Press, 1990), 407-410; and Robert Merrill MacLean and Sean Rossiter, Flying Cold: The Adventures of Russ Merrill, Pioneer Alaskan Aviator (Fairbanks: Epicenter Press, 1994), 163.

- Charles C. Hawley, “Arthur A. Shonbeck (1878-1945),” Alaska Mining Hall of Fame, 4.

- Charles Caldwell Hawley, Wesley Earl Dunkle: Alaska’s Flying Miner (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2003), 155-156.

- “Grand Opening Anchorage Fair Occurs Tonight,” Anchorage Daily News, August 30, 1924, 1.

- “Arthur A. Shonbeck," UA Journey.

- Michael Carberry and Donna Lane, Patterns of the Past: An Inventory of Anchorage’s Historic Resources (Anchorage: Community Planning Department, Municipality of Anchorage, 1986), 136. On page 21, Carberry and Lane give a brief description of his earlier residence, a small bungalow dating from 1916, that was later incorporated into the Munford Building, a two-and-a-half story structure at 135 Christensen Drive, Anchorage.

- Charles C. Hawley, “Arthur A. Shonbeck (1878-1945),” Alaska Mining Hall of Fame, 6; and “Shonbeck Rites are Set for Next Sunday,” Anchorage Daily Times, June 22, 1945, 1 and 8.

- Entry for Mrs. Ann Shonbeck, “End of the Trail,” Alaska Sportsman, April 1964, 45.

Sources

This biographical sketch of Arthur A. Shonbeck is based on an essay originally published in John Bagoy’s Legends and Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1935 (Anchorage: Publications Consultants, 2001), 97-98. See also the Arthur A. Shonbeck file, Bagoy Family Pioneer Files (2004.11), Box 7, Atwood Resource Center, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Anchorage, AK. Note: edited, revised, and expanded by Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, October 15, 2014.

Preferred citation: Walter Van Horn and Bruce Parham, “Shonbeck, Arthur A. ‘Art’ or ‘A.A.’,” Cook Inlet Historical Society, Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, http://www.alaskahistory.org.

Major support for Legends & Legacies, Anchorage, 1910-1940, provided by: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, Atwood Foundation, Cook Inlet Historical Society, and the Rasmuson Foundation. This educational resource is provided by the Cook Inlet Historical Society, a 501 (c) (3) tax-exempt association. Contact us at the Cook Inlet Historical Society, by mail at Cook Inlet Historical Society, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, 625 C Street, Anchorage, AK 99501 or through the Cook Inlet Historical Society website, www.cookinlethistory.org.